-Co-authored with Derin Adebayo

The authors of this essay first met nine years ago during a weekend hangout at Hotels.ng. Derin worked there in finance, while Osarumen worked down the road at TechCabal. Just months earlier, Hotels.ng closed its $1.2M Series A from Omidyar Network & Echo VC–one of the biggest rounds in 2015, which made it one of the best-funded startups on the continent. What seemed monumental then doesn't even merit a headline now.

About 171 startups raised >$1 million in 2023 / Image Credit: The Subtext

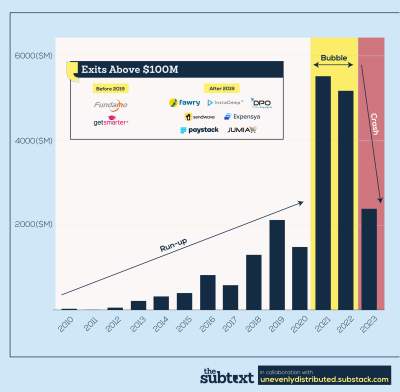

According to data from Partech, African startups went from raising $320M in 2014 to peaking at $5B+ in 2021 (a nearly sixteen-fold increase in seven years). Like other tech ecosystems, the continent was flush with capital in the wake of the COVID pandemic. It’s been a rocky ride down, as the global venture ecosystem faces fundamental questions about the past few years. One question, in particular, has become more pressing in Africa: “Where are the exits?”

-

We first addressed this in The Chicken or The Exit? (2021). Our premise was that venture capital ecosystems mature in phases and that the African ecosystem was still nascent. We argued it was too early to expect consistent liquidity until the ecosystem produced more mature companies:

Illustration of the 'ecosystem maturity framework' (2021)

In the three years since we wrote that essay (2021 - 2023), African tech has brought in $12B of capital, roughly double the amount raised in the prior 11 years. During this period, the continent has generated only a handful of significant exits. This is not the case with other emerging venture ecosystems. During the recent peak, Latin America saw the IPOs of companies like Nubank & dLocal; South-East Asia had GoTo, Bukalapak, & Grab; in India, Zomato, Delhivery, Nykaa, PolicyBazaar & Paytm all went public in the same period. While these ecosystems are still maturing, they are clearly at different stages. Over the past decade, India has been the only major market to show consistent growth in public market listings. In 2024 alone, 12 startups, including seven technology firms, have gone public, according to data from PitchBook.

Where does this leave Africa? The chart from 2021 probably looks something like this today:

Illustration of the 'ecosystem maturity framework' (2024)

When a technology ecosystem generates hype, it is always followed by the expectation of increased liquidity. The hype comes because people believe it has the potential to generate outsized returns. It is only considered mature when it delivers on those expectations, with capital flowing consistently into companies and back out to investors. But if said ecosystem does not validate itself, it enters decline.

With four years and $12B since we wrote the first piece, it is difficult to claim that Africa is still nascent. Is it yet time to ask, 🔫 “Where are the f%#$ing exits?”

Not quite.

Riding the waves

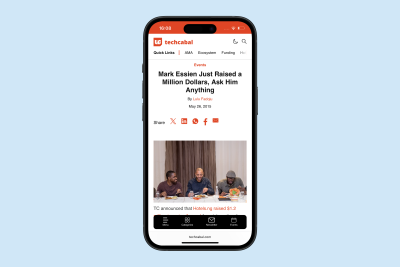

Venture capital is a highly cyclical asset class. Each cycle begins with a run-up, where investments rise slowly but steadily over an extended period. Then, there is a bubble, a period of exuberance, where investments (and valuations) increase rapidly for a few years. Inevitably, this is followed by a crash, which resets the cycle and kicks off the next run-up. You can see three of these in the chart below showing US venture investments over the past 25 years:

Source: Pitchbook & NVCA

A fascinating feature of the venture asset class is that most of its over-performance comes during these brief periods of madness. During a bubble, inflated expectations and heightened deal activity create exit opportunities for investments made during the run-up. If you remove these bubbles, VC becomes a much less interesting asset class. Bill Gurley lays out this argument in an appearance on the All-In podcast (1:03:19):

Applying the ‘venture cycles’ mental model to African tech makes it clear that Africa is still in its early days. The continent just completed its first full cycle. Pinpointing the start of a venture ecosystem is highly subjective. However, we consider this one to have started in 2010–the earliest we could find reliable data on venture investments on the continent. That year, the entire continent raised $35M, according to VentureBurn. Within four years, the number grew to $320M. By the end of 2017, total venture investments were still below $1B.

It was during this period that the first conversations about a “lack of exits” emerged. Of course, these conversations were grossly premature. Given the typical venture exit takes ~eight years, it should not have been surprising that there were no significant exits by the end of 2018. Then, Jumia went public in 2019. By October 2020, Stripe announced its $200M+ acquisition of Paystack. Within 33 months (October 2020 - July 2023), the continent saw five major acquisitions (Paystack, DPO, Sendwave, Expensya, & Instadeep) that almost perfectly coincided with the peak years of the cycle¹.

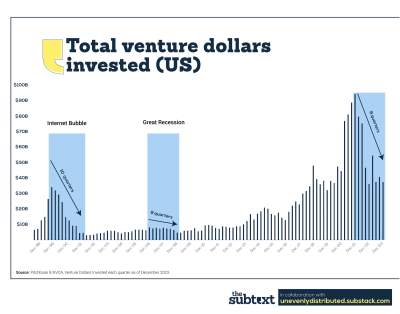

From a return on investment perspective, these exits mean that 2010-2017 should be seen as a massive success for African tech. 587 companies raised $2.4B in this period, and just five of them generated ~$2.5B in exit value²:

Jumia (IPO’d at $1.12B)

Sendwave (acquired for $500M)

Paystack (acq. $200M)

Instadeep (acq. $549M)

Expensya (acq. $120M)

There is also >$6B in unrealized value from three other companies: Andela ($1.5B), Wave ($1.7B), and Flutterwave ($3B). If African VC from 2010-2017 was a fund, these eight companies should easily return the fund.

Analysis by Derin Adebayo / The Subtext

-

Of course, the ecosystem did not end in 2017.

2018 was a major inflection point for the continent. It was the first year African startups raised over $1B. The following year, they brought in $2B; by 2021, the number ballooned to $5B. Altogether, between 2018 and 2023, the ecosystem attracted $17B in venture capital–seven times the $2.4B raised in the prior seven years.

While exits leading up to and during the bubble have returned the 2010-2017 investments, it is clear that the volume of exits must now rise dramatically if the ecosystem is going to return the investments from 2018-2023.

Africa's first full venture cycle (2010-2023)

Blitzscale 101

As capital flooded the continent post-2018, a new kind of African startup emerged, with >$100M rounds and $1B+ valuations. Flutterwave, Chipper Cash, OPay, Wave, Interswitch, and MNT Halan, all raised mega rounds and became unicorns in that period. Others like Moniepoint, Tyme Bank, Yoco, Kuda, Wasoko, and Yassir didn’t quite hit the ‘B’ but seemed well on their way there. (The first two have since joined the vaunted unicorn club.) This cohort–let’s call them ‘blitzscalers’–accounts for a significant chunk of the capital raised between 2018 and 2023.

Source: Africa: The Big Deal

If the exits of Paystack, et al. validated the run-up (2010-2017), then the exits (or failures) of the blitzscalers will determine how we remember the bubble years. Unlike their predecessors, blitzscalers have raised capital and hit valuations which mean that only (multi-)billion dollar outcomes will be seen as “successful”.

Paystack, Sendwave, and Instadeep proved that Africa can generate exits. Flutterwave, Andela, Wave, and OPay proved that Africa can generate unicorns. If the continent is going to deliver a return on the investments from 2018-2023, it must do something unprecedented: generate exits for unicorns.

-

Global capital, local reality…

The venture model faces a unique contradiction in developing markets: while businesses are typically focused on their home turf, the majority of the capital comes from foreign investors. Even “local” VC funds raise most of their capital from foreign LPs. As Stephen Deng points out in this article:

“Much of this capital came from global investors new to Africa, bringing with them Silicon Valley’s ZIRP³ era archetypes and models. In 2021, 77% of active investors in Africa were international.

A young ecosystem naturally shapes itself around the vision of its funding sources, and African tech has been no exception.”

While a company may try to align with its investors' expectations, it must ultimately operate within the constraints of its environment. This creates a tension for African businesses, most visible when it’s time to exit: they must bridge the gap between global investor expectations and local market realities.

Exiting globally–by listing on a foreign stock exchange or getting acquired–usually involves explaining the realities of your market to potential investors who don’t quite understand it. Meanwhile, exiting locally means justifying the valuation of a venture-backed, high-growth technology company to an audience unaccustomed to paying such rich multiples.

Over the next decade, the ecosystem must solve this fundamental tension or see its best funded companies enter a late-stage purgatory.

An acquired taste

Paystack was acquired by Stripe, DPO was acquired by Network International, and Sendwave was acquired by WorldRemit.

These three have a few things in common–traits they share with the vast majority of VC-backed exits on the continent: they were relatively capital-efficient businesses⁴, acquired for under $1 billion.

Scaling a startup in Africa requires cultivating deep local expertise, execution capacity, and business/regulatory relationships. In the right hands, this could be an extremely valuable asset. However, to be a viable acquisition target, the asset must be built efficiently. The more capital a company raises–the higher its valuation, the less likely it exits via an acquisition. The majority of acquisitions happen before Series B stage, so intentionally or not, early rounds shape a company’s eventual exit options.

Source: Pitchbook-NVCA Venture Monitor

In 2019, Paystack and Flutterwave were similar businesses at roughly similar stages of their journey. Paystack was acquired by Stripe for $200M about a year after Stripe led its $7M Series A. Flutterwave, meanwhile, went on to raise a further >$400M and hit a valuation of $3B (2022). Both companies are incredibly successful and, in different ways, raised the standard for what is possible for an African startup. However, by raising more capital, Flutterwave has committed to a path that means it is more likely to exit through an IPO than an acquisition.

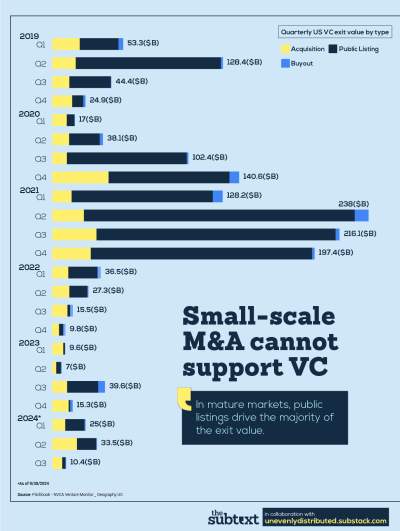

Flutterwave’s trajectory is typical of blitzscalers–their capital raises and valuations are beyond the reach of most acquirers. The same is true at the ecosystem level. When billions flow into an ecosystem, only IPOs can generate exits at the scale required to sustain that investment:

Quarterly US VC exit value by type (2019 - 2024)

🌍 Going global

For many founders, ringing the bell at the NASDAQ or NYSE is the ultimate dream. Going public on a global stock exchange confers legitimacy and unlocks deep pools of capital looking to invest in fast-growing technology companies. However, businesses on the continent looking to access these pools face a daunting task: only a handful of African companies have ever made it across the road.

Investors participating in these markets have limited context about the continent. To them, Africa is terra incognita—only companies with easily comparable business models stand a chance. It is easier to get a US public markets investor to commit to the Stripe/Amazon/Uber of Africa, than a company where both the business model and the geography are unfamiliar. This tends to favor African companies with globally recognizable models–SaaS, consumer, fintech–and those without the operational complexity often seen in emerging markets.

That said, a familiar model doesn’t guarantee a global IPO. You also need a certain level of scale. Most African businesses are simply too small in USD terms to matter to global investors. The most prominent scale-ups on the continent have valuations under $5B; if listed on Nasdaq or NYSE, they would all be considered small-cap companies.

There was a recent conversation on US Tech Twitter about whether “subscale” software businesses can/should go public. The most striking part of the discussion was that $150M revenue was considered subscale. Probably fewer than 20 African startups have ever reached that level–realistically, those are the only companies with any chance at a global IPO.

Look! A Local Listing!

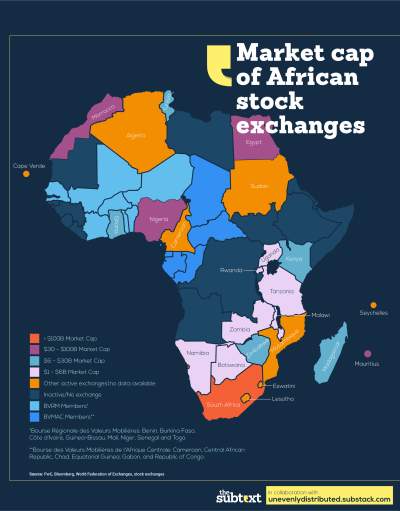

But what would an African startup IPO look like? We’ve recently seen WeBuyCars and Fawry go public in Johannesburg and Cairo. Listing locally gives these companies access to investors who understand their market. A B2B e-commerce platform or agent banking network would find it easier to explain its business model in Lagos, Cairo, or Joburg than New York or London.

However, while local investors might understand these businesses, convincing them to accept VC-backed valuation multiples is much harder. African scale-ups would be small fish in global public markets, but on local exchanges, they’d command valuations (and multiples) that dwarf those of other listed companies. Take Flutterwave and Andela - they would be among the top ten companies on the Nigerian Stock Exchange by valuation, with multiples far exceeding their peers.

Even if a company were to settle for a lower valuation/multiple, liquidity remains a significant challenge in Africa. With the exception of Johannesburg, most capital markets on the continent are relatively shallow/illiquid. Between them, Nigeria and Egypt have three stock exchanges worth ‘only’ $100B combined (less than 1 Uber). In fact, remittances to Africa in 2018 alone ($40B) were 5x the total amount raised via IPOs between 2017-2021 ($8.1B).

PwC / The Subtext

-

Where next?

For the blitzscalers, it may seem like we’re painting a bleak picture. They have largely outgrown acquisition; they’re too big for local stock markets, while in global markets, they risk drowning among multi-billion dollar giants. For some, there will be consolidation. Others will see slowing growth (if they haven’t already) and become zombie companies. This is not unique to Africa. The global start-up ecosystem is going through a reset after the exuberance of the ZIRP era. Founders and investors are still figuring out how to land the plane.

But it's not all doom and gloom. We expect to see one significant global IPO from the continent in the near future.

- The most obvious candidate is Flutterwave. It has a well-understood business model and publicly listed peers such as Adyen, Network International & dLocal. It is also visibly preparing. If long-private fintechs like Stripe or Checkout.com go public in the coming years, that will create an additional tailwind for the African payments company last valued at $3 billion.

- There are already three publicly listed fintechs on the continent–they’re just hidden within mobile operators. Airtel, MTN, and Safaricom have all floated the idea of (‘-‘ )(>_>) floating their mobile money arms. Still, it’s just as likely that the continent’s first publicly listed mobile money or agent banking operator will be an independent fintech. Wave, Opay and Moniepoint are also potential candidates. A successful IPO by any of these companies could spark another ‘Paystack moment’ for the ecosystem.

‘Invested Infrastructure’

In part 1 of this series, we argued it was important to see companies get to scale before worrying about exits. Today, we have a cohort of companies that have achieved scale, or at least, capital and valuations that suggest scale. However, the drunken environment in which these valuations were set means that their connection to fundamentals is uncertain at best.

While this generation navigates the ZIRP hangover, there are multiple reasons to be excited about what comes next.

- Over the last decade, 800 African founders⁵ raised venture capital. They experienced the heady highs and the comedown after. They’ve made mistakes, paid school fees, and hopefully learned important lessons. Those who remain will enter the next cycle battle-tested.

- Meanwhile, the local investor ecosystem has never been stronger. In The Chicken or The Exit, we took Partech’s $143M and TLcom’s $71M funds as signs of a sophisticated investor base developing on the continent. Both firms have since closed new funds, as have others like Norrsken22 and Breega. While global investors are taking a step back, there has never been more dry capital committed to this market⁶.

Beyond the founders and investors, financial bubbles are–themselves–critical to the deployment of technology. The excitement drives investment in critical infrastructure that would otherwise be considered uneconomical. During the dotcom bubble, American telcos invested heavily in fiber-optic infrastructure, expecting an explosion in consumer internet usage. After the crash wiped out those investments, the cheap and abundant ‘dark fiber’ left over enabled Google to start building out its infrastructure network. It is hard to imagine YouTube today without the overinvestment of the late 1990s.

"Invested Infrastructure" - by Kehinde Owolawi, for The Subtext

Similarly, investments into African tech over the past decade have laid the foundation for deeper digital adoption. The boom years attracted ambitious talent into the ecosystem–engineers, product managers, marketers, and operators, drawn by the industry’s rising prospects. Agent banking platforms like Wave, Opay, Mpesa, and Moniepoint have extended financial access to the last mile, where digital payments are now part of daily life. B2B e-commerce platforms have built out logistics networks reaching millions of SMEs. Gig-work platforms have trained a cohort of digitally-savvy young Africans, making deliveries, doing customer service, and selling offline. Brick by brick, the foundations have been laid for the next phase of the continent’s technology ecosystem.

-

Long road ahead

In March 2024, FT Partners held its Fintech in Africa forum in New York. Over two days, company after company after company made their case to a room of investors. Most had revenue in the tens of millions, and a few, over a hundred million. Almost all of them were still growing.

If you told us a decade ago, when we sat at hotels.ng discussing ’African tech’ that there would be multiple startups on the continent generating over a hundred million dollars, we would not have believed you. If you told us that we would have multiple companies generating over a hundred million AND we would still be wondering ‘whether the venture model can work on the continent,’ we would have laughed you out of the room.

The chickens have yet to cross the road. The exits have yet to come, at least not at the size and scale we want. The next few years will involve painfully working through the overexuberance of the past. But the signs of progress are undeniable, and there is plenty of reason to look forward to the next decade of African tech.

-

With love in our hearts,

-Derin and Osarumen

Thank you to Eloho Omame, Kola Aina, and Fope Adelowo for speaking to us while we worked on this; Precious Amuta for helping with the research; Ifedoyin Shotunde for the cover illustration; and Kehinde Owolawi for art direction/essay graphics.

Footnotes

1. The boom years also drove M&A within the ecosystem. For example, Onafriq/MFS Africa completed four acquisitions between 2020 and 2022: Beyonic, Baxi, SimbaPay, and GTP (🇺🇸)

2. Returns from the 2010-2017 vintage are a clear example of the “power law” in action

3. ZIRP (Zero Interest Rate Policy) refers to the period (2009-2022) when major central banks kept interest rates near zero, making capital unusually cheap/abundant. This drove more risk taking with investors around the world, and enabled aggressive startup funding strategies that prioritized growth over profitability.”

4. Of this cohort, Instadeep raised the most capital pre-exit. However, $100M of the total $107M it raised came the year before being acquired. Instadeep only raised $7M in its first seven years of operation.

5. According to Africa: The Big Deal

6. This matters > because local investors are likely to be nuanced about how they deploy capital. At exit, they will also be better at bridging the gap between local market realities, and the largely foreign VC model