This essay was co-authored with Derin Adebayo

Venture Capital has an Unlikely Ancestor

Two hundred years before Silicon Valley became the holy land for technological innovation, ship captains in New Bedford, USA funded whaling expeditions by raising money from the wealthy. Those with the stomach for it would invest through whaling agents who arbitraged between access to capital and access to information. Some version of this system still exists today:

- Skilled operators undergoing a difficult (but lucrative) journey, needing resources upfront

- Capital providers ‘hiring’ middlemen (sadly, almost always men) who know where and how to find the best operators

- The middlemen earning a small fee upfront to facilitate the investment, but with the majority of their compensation coming from the profits of the venture

Sound familiar?

Figure I - The basic organizational structure of Whaling and Venture Capital. Source.

As with startups today, success in whaling was often rewarded with life-changing wealth. But unlike modern business, you often paid for failure with your life. One would have to be mad to go on a whaling expedition, and indeed, the whalers were often out of their minds:

The [Essex whaleship] left Nantucket in 1819 and sailed for over a year before being destroyed by a whale it was hunting. [...] At first the [surviving crew] buried the dead at sea; then they resorted to eating the corpses of their crewmates. When they ran out of bodies, they drew lots to decide whom to shoot and eat. Only five of the 17 were eventually rescued. By then, they were so delirious that they did not understand what was happening.

Why would anyone put themselves through such trauma? Well, for the “fabulous profit” that could be made.

Gideon Allen & Sons, a whaling syndicate based in New Bedford, Massachusetts, made returns of 60% a year during much of the 19th century by financing whaling voyages—perhaps the best performance of any firm in American history. It was the most successful of a very successful bunch. Overall returns in the whaling business in New Bedford between 1817 and 1892 averaged 14% a year—an impressive record by any standard.

Whaling was so profitable because whales “contained abundance”, i.e. each whale caught and brought to shore provided body parts that fed many value chains across the economy: they were killed for meat; whalebone from the upper jaws of baleen whales was used to make baskets, corsets, fishing rods, and umbrellas; the teeth of certain species were carved to make piano keys and chess pieces; oil from whale blubber was burned to provide lighting, used as a lubricant in clock-making, and to manufacture soaps and cosmetics; grey amber/ambergris from sperm whales was used to make perfumes and cosmetics; and so on.

Similarly, by making distribution free* and unencumbered* (*sort of), the internet created the opportunity for even more fabulous profit. Facebook has roughly 3 billion users, and Google has 9 products with over a billion users each. Perhaps more importantly, there is almost no cost for either company to serve each additional user (i.e. zero marginal costs). At the time of this writing, Facebook and Google are the 5th and 6th most valuable companies in the world. They are just two of five internet companies in the top 10. For software companies distributed through the internet, the addressable market is the entire world. That is to say, it contains abundance.

Whalebone/Baleen. Source.

Like whaling, technology entrepreneurship ordinarily shouldn’t work. Founders shouldn’t forgo stable incomes at large corporations for the uncertainty of a new/risky venture; developers and other team members shouldn’t stake their most productive years working for companies that may not exist in less than a decade. But people start or join startups for the same reason crews go on whaling expeditions - a little madness, some excitement, and a tiny chance at a massive return[1].

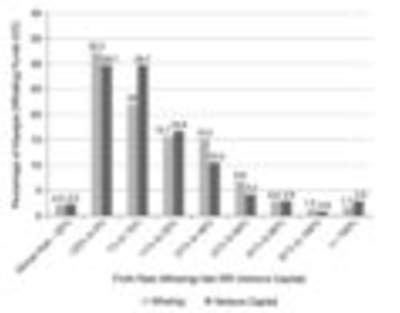

Crucially, in startups, like in whaling, most ventures do not actually deliver these expected profits. Venture Capitalists famously say that their returns follow a “power law distribution” i.e., that the vast majority of returns are generated by a small number of firms, and that the majority of each firm’s returns are generated by a small number of companies. (Chris Dixon calls this the “Babe Ruth effect”, after the American baseball player; his essay is a good primer on the topic. Jerry Neumann, here and here, goes quite a bit deeper.)

Figure II - The distribution of returns in Whaling and Venture Capital. Source.

There is, though, an important difference: in whaling, the potential downside (loss of life) is infinite, while the upside is constrained by the size of the vessel[2]. In tech VC, on the other hand, the downside is limited (you only lose the money/time you invest), while the potential upside is unbounded.

Because of the limited risk and unbounded upside, it has become conventional wisdom to make as many bets as possible in early stage VC. Dave McClure makes this case: “If we surmise that unicorns happen 1-2% of the time, [then] it is logical to adopt a portfolio size that includes at least 100 companies.” After all, if Jason Calacanis can make $100m from a $25k investment in Uber; if Lowercase Capital’s $300,000 investment in 2009 was worth $1.9 billion at IPO, then it almost doesn’t matter what else they invested in.

Internet, Meet World

It’s difficult to argue against the success of the venture capital model pioneered in Silicon Valley. Eight of the ten most valuable companies in the world are venture backed. According to a 2015 study by researchers from Stanford University, 42 percent of public companies are venture backed, representing 63 percent of total market capitalization. These companies account for 35 percent of total employment and 85 percent of total research and development spend.

Naturally, many countries/regions have tried to build the “next Silicon Valley”, to varying degrees of success. The result, though, is that the internet is increasingly less American, and consequently, so are internet companies. They’re springing up in France, Israel, China, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Egypt, Nigeria, and many other countries in between.

Venture Capital investments: USA vs. Rest of World. Source.

In her 2002 book, Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital (pp. 63), Carlota Perez broadly describes this phenomenon:

As paradigms mature in the core countries, investment opportunities move further and further out, seeking comparative advantages, different conditions and possibilities for outstretching saturated markets.

It would seem that each paradigm spreads in ripple-like fashion, both from sector to sector across the industrial structure and geographically inside each country and across the world.

But as tech VC travels from core to peripheral markets, the opportunities it finds are increasingly regional (rather than global), in problem spaces where distribution is not necessarily free or unencumbered, where zero marginal costs are not always the reality, and where software isn’t necessarily central to the companies’ operating model. Companies in these markets are often called “tech-enabled”, rather than technology companies.

A good illustration of this phenomenon is Stripe, which currently operates in about 40 countries, and is rumoured to be raising a round at a $100B valuation. The company has scaled to a large portion of the developed world on the basis of the invested infrastructure existing in those countries. It has found it much harder to expand into markets without that infrastructure.

Stripe’s efforts in emerging markets have been limited to a handful of offices, and investments in the Stripe of South-East Asia, and the Stripe of Africa. What is notable about the payments landscape in Africa and South-East Asia, though, is the relatively high cash usage and fragmentation of payment methods across countries. These complexities increase the cost of distribution and effectively limit companies to a largely regional focus.

Venture returns are driven by the upside from companies that achieve massive scale. The complexity of operating in emerging markets means that very few emerging market technology companies will achieve similar scale to Stripe, at the very least, until the necessary infrastructure is built[3].

As a venture capitalist operating in an emerging ecosystem, then, you are faced with the challenge of generating returns in a market where your breakout successes aren’t valued at $100B but at $200M. A common response is that a completely different model of funding needs to emerge for African companies. We don’t think this is necessarily true. In reality, investors in Africa only need a slightly different approach from their Silicon Valley peers.

A $25k investment into Paystack’s seed round would have generated great returns at the deal level, but might not have generated returns at the fund level if the fund adopted a spray-and-pray approach.

Africa-focused VCs’ portfolio construction must, therefore, recognise the reality that we will not have as many exits as a more mature market and that the exits we have will be much smaller. In effect, such a fund’s performance becomes less about the number of companies it invests in, and more about how much money it puts into the right companies.

One fund that executed this approach is the Latin American venture firm ALLVP, which was able to generate strong returns investing in a nascent Mexican tech ecosystem from 2012. General Partners, Federico Antoni and Fernando Lelo de Larrea raised $6m for their first fund, backing 12 companies, and holding 10%-49.9% stakes in them. That fund saw two modest exits, but their high equity stakes meant that they probably easily returned the fund. Their second fund, sized at $36m, has been the real blockbuster. With an average ownership of 18.5%, it has seen two exits, Aplazame (acq. by digital bank WiZink) and Cornershop, a grocery delivery firm, partially exiting to Uber for $450M. The latter, likely returning 2x the entire fund due to the amount of capital they had put in the right company.

ALLVP’s investment into Cornershop represented 25% of their total funds allocated to new investments. You would be hard pressed to find a Silicon Valley early stage VC with that much of its capital concentrated in one portfolio company.

Scale before Exits

Emerging ecosystems have largely adopted the Silicon Valley venture capital playbook. But these ecosystems are at different stages of maturity and need to find a playbook tailored to their stage.

However, ecosystem maturity is not a tangible phenomenon, and is therefore challenging to measure. Current entrepreneurship literature, just like the drunk searching for his keys under the lamp-post, typically looks where it can see, relying on visible proxies like the amount of capital raised and the number of hubs, startups, or developers.

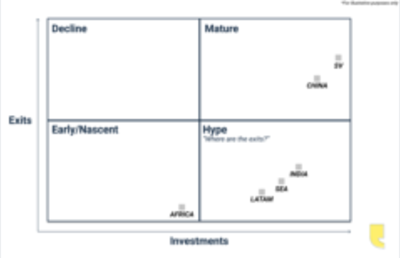

A more useful lens can be derived from something any entrepreneur would be familiar with: the journey of an individual startup. Like startups, ecosystems go through three distinct phases: experimentation, scaling, and liquidity. Each phase is characterized by the type/amount of capital that flows into an ecosystem, what kinds of companies it is funding, and whether it is readily generating exits. We can visualize this using a simple 2x2 matrix.

Figure III – The Ecosystem Maturity Framework

Nascent ecosystems (bottom left) are focused on experimentation. There are no exits yet, and there is little investment to speak of. The contours of the market are not yet clear, and so founders test business models typically copied from more developed ecosystems. The capital at this stage comes from impact investors, local angels, and a handful of adventurous firms dipping their toes into the market.

In the mid-2010s, the Nigerian ecosystem was dominated by this type of capital, funding businesses that introduced a digital layer to offline industries but didn’t fundamentally reorganize their value chains. We had hotels, but online. Apartments, but online. Nollywood, but online. Printing, but online.Everything, but online. And so on. Over time the ecosystem learned, among other things, that simply connecting demand to fragmented supply via the internet was not sufficient to achieve scale.

By the next phase, lessons like the one above are internalized by a new generation of founders who build businesses more tailored to their local contexts. Investors become more sophisticated, learning about the contours of the market from the first set of experiments. Local GPs began to emerge, raising large funds to deploy capital into Series A and B rounds for businesses that have found product/market fit. Average round sizes increase, and investment into the ecosystem soars.

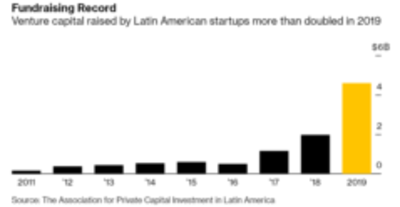

This stage is best illustrated by the Latin American ecosystem, where investment grew steadily from 2011 till 2015, before experiencing exponential growth in the past four years increasing from $500M in 2016 to $4.6B in 2019. Per the framework above, this is also where you start to see concern about a lack of exits: the amount of investment far outpaces liquidity for investors.

Venture capital raised by Latin American startups (2011 - 2019)

This is also where things get interesting. Ecosystems truly take off when the bets taken by the first two groups of investors begin to pay off. Global players enter the market to fund scaling businesses primarily seeking more growth and eventual liquidity. At this stage, capital accumulates behind the proven winners, average ticket sizes go up even further, and valuations follow. The chickens have come to roost, and the exits follow. Unicorns emerge, and start to acquire smaller companies as they drive to consolidate and become regional winners. (Aside: Interswitch is reviving its venture fund and recently hired a Head of Mergers and Acquisitions.)

South-East Asia acquisitions

South East Asia had its first unicorn in 2014, by 2019, nine SE Asian unicorns had acquired 28 companies. Global strategic players, awakened to the attractiveness of the region, start to make heavy investments and acquisitions. Global financial players, looking for the kinds of attractive returns that can only be found in emerging markets, start to make more late-stage investments, and drive exits by pushing their portfolio towards IPOs and M&A. The final stage is where the most mature markets like China and USA are, where a steady flow of capital exists to reliably move companies from seed stage to eventual exit.

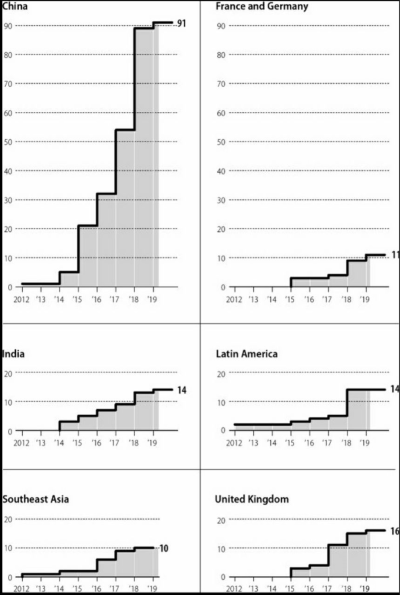

Number of unicorns v. Year for different regions

This is why the conversation around a lack of exits in Africa is premature. Ecosystems have to go through experimentation and scaling before liquiditystarts to emerge. This process is well on its way in the African ecosystem. The past few years has brought the rise of sophisticated African early stage VC funds (here, here, here, here), total funding into the ecosystem is starting to accelerate, and global financial (here, here) and strategic (here, here) investors are starting to take an interest in the continent.

However, even the most optimistic estimates would put Africa firmly in the experimentation stage or the beginnings of the scaling stage. The continent only just had its first unicorn. China had its first unicorn in 2010, and it took five years for it to get to five unicorns; the year after that, it had twenty. Ecosystems develop very slowly, and then all at once. As startups build infrastructure using technology, they inadvertently create new markets. We’ve seen this happen in China, South East Asia and Latin America, it’s only just beginning in Africa.

Notable exits in African Tech (2011 - 2019). Analysis by The Subtext. Data sourcing by TC Insights.

With love in our hearts, and COVID-19 test swabs up our nostrils,

Osarumen & Derin.

FOOTNOTES

- There also exists an ecosystem such that if a start-up fails, or a whaling expedition returns empty handed, there will be other willing backers for the next one. Indeed, many funds prefer to back second-time founders.

- For example, in 1871, the captain of the whaleship Myra reportedly dumped a hundred barrels of whale oil overboard after coming across sperm whales which would have been worth much more.

- There are other important issues like gdp per capita, consumption et al, but these are the issues relevant to the argument being made here.