Transsion Follow-Up

If the conclusion of Transsion’s Trojan Horses felt hurriedly-written, that’s because it was. Till date, it has been the most shared Subtext article (asides from the manifesto, natch) but I can’t shake the feeling that I didn’t do a good enough job of framing it. Specifically, let us revisit this bit:

"But zooming out, we are witness to and participants in a global race to own the African consumer. Today, most of their economic activity is centered around the bottom of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, but the expectation is that they will move up to higher value activity, and the companies that own them then will be that much better off for it.”

The phrase “own the African consumer” carries predatory connotations I didn’t intend -- especially considering recent history. A much better way to capture my meaning would have been, “... a global race to build a direct relationship with the African consumer.” But the other reason it made me uncomfortable is that it’s also not very accurate. To see what I mean, let’s examine the second part of that excerpt.

Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs. Source: Simply Psychology

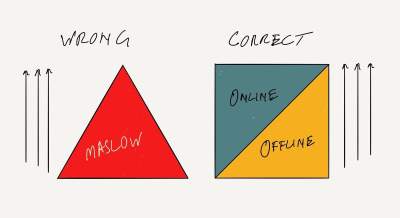

It would be a little simplistic to argue that low-income African consumers only have needs at the bottom of Maslow’s pyramid. In reality, they are multidimensional; with creative abilities, emotional needs that need fulfilling, hopes, fears, and aspirations, just like everyone else. More importantly, they spend money and engage in economic activity to fulfil all these needs. That their economic calculus often feels counterintuitive to outsiders does not mean it is invalid. What I did mean to communicate, though, was that the bulk of these low-income consumers’ activity happens offline, and that over time they will do more and more online, using digital mediums. This looks more like the diagram on the right than the one on the left, and the race between global firms is to establish a relationship with them before they move to the top and those behaviors ossify.

Illustrated by Osarumen Osamuyi for The Subtext

There is one more reason why this clarification is important. Many of the global companies vying for African consumers’ attention are leveraging their unique distribution advantage (e.g. Opera starting with their browser, Transsion starting with their phones, and WhatsApp starting with the most-used messaging app in the world) to deliver financial services to them, and this correction makes it clear why.

- If these companies are preparing for a future where consumers across Africa spend much more of their time on the internet, then they must fix the plumbing -- invest in the infrastructure that lets them capture value from their bases in Silicon Valley or China ante tempus.

- More importantly, if these consumers do everything offline with the people they care about the most, then technology companies must insert themselves into their lives by enabling activity that originates offline, namely i) communications with the people they care about the most, ii) payments or value transfer between them and others they transact with. (Or, in the case of WhatsApp, both.)

This is why the stakes are so high, and why local startups should pay attention. Low-income African consumers will be brought into the digital age, and that will create new needs -- needs that Facebook, Google, Opera, Transsion, Truecaller etc., are ill-equipped to satisfy, but local entrepreneurs with cultural context can take advantage of.

This, to my mind, is a more compelling bull case than mere ‘smartphone penetration’. It helps describe not only the fact that Africans will come online, but gives us an idea about what kinds of services to build today. More about this in a later post.

Opera's Big Balloon

There is one global player whose approach to this opportunity I find fascinating -- Opera. The company’s strategy is best described as a balloon; if you squeeze one part of a balloon, the air would not cease to exist, but will flow to other parts with less resistance. Why does this matter?

Today, for most of the developing world, Facebook is synonymous with “the Internet”. The majority of African internet consumers live wholly within Facebook’s ecosystem -- the Facebook social network itself, WhatsApp, Messenger, and more recently, Instagram. This gives the company much more leverage than most in the race described above. Facebook has quickly become communications infrastructure for the majority of the continent online.

This puts other global players at a disadvantage, as Facebook’s pull is not intrinsic to the product itself, but in the fact that it is a means for its users to reach the people they care about the most, and find interesting content to consume.

Source: TechCrunch

Enter, Opera. In April 1995, two Norwegian developers, Jon Stephenson von Tetzchner and Geir Ivarsøy started the company to continue work on a research project at Telenor, Norway’s largest telecoms operator. Version 1 of the product only ran on Microsoft Windows, but the broad vision was to make access to the internet universal. According to the company’s archives, it started a project to port the browser to handheld internet-connected devices in 1998, and released its first cross-platform product in 2000.

In 2005, it introduced Opera Mini, a Java ME based mobile browser, marketed to telco operators to bundle with the devices they sold. The Mini browser doesn’t request web pages directly, but through Opera’s own compression proxy server before pushing them to the device. The effect is that pages load many times faster, and consumes drastically less data than other browsers -- a key feature for low-income consumers.

Fast forward to 2016, and Opera had amassed over 100 million users in Africa, with 70% of Facebook’s Nigerian users accessing the social network via the Opera mobile browser. The social network launched its Facebook Lite app in June 2015 to mitigate against exactly this kind of threat and continue its march to become “the Internet”. If Facebook succeeds in cementing its place as the gateway to all online activity for consumers coming online in Africa, then Opera will see its usage go down and it will lose its leverage.

Thus, Opera has to become Facebook (utility), before Facebook becomes Opera (gateway to the internet). How does it plan to achieve this?

Last year, the company announced it was investing $100 million to grow its business in Africa and make its browser a media platform. In the same vein, making web pages data light by stripping away Javascript code improves the browsing experience for low-income users and helps Opera squeeze the big balloon -- create a choke point and position itself as the front page of the internet.

This, in turn, creates opportunities to determine what content they see (which they are now trying to do with their Opera News app -- the subject of a separate post), build an advertising business around content consumption patterns, but also to enable value transfer via payments.

Viewed in this light, launching OPay, a payments wallet for Kenya, and acquiring a controlling stake in PayCom, a Nigerian mobile money platform begins to make sense. By squeezing the balloon in one area (destroying monetization for publishers, becoming a media platform to own attention, and serving as the front-page of the internet), Opera is letting value flow elsewhere, and positioning itself to capture it. Now, we wait, popcorn-in-hand and drink-straw-in-mouth for the results of this experiment.

--

That’s all for today. Please share this edition if you liked it. Thank you for reading!

With love in my heart and Blackbell coconut rice (+ three pieces of beef) in my belly,

Osarumen.