How do you think about motorcycle taxi hailing in Africa? If you were like me three years ago, you mostly didn't — it hadn't become one of the sectors du jour, and our collective love affair with fintech had only just begun. But from 2017 through '18, pockets of activity started to show up on the continent: MAX, originally an on-demand logistics service from Nigeria, announced MAXGo in mid-2017; its main competitor, Gokada, would launch seven months after. 3000+ kilometers away in Uganda, SafeBoda overhauled their technology and kicked off international expansion the following year. With backing from the Rwandese government, Yegomoto started rolling out their taximeters to Kigali's 15,000+ motorcycle taxi drivers, while global players like Uber and Bolt/Taxify joined the fray with their boda boda offerings in Kampala and Nairobi.

These startups present their products in ways that reflect the cultures and assumed customer needs in their countries of origin. East African players, for example, generally threaten to bring safety and sanity to a boda industry mired in chaos (see: Uganda's "Safe"-Boda and Rwanda's "Safe"-Motos), while their counterparts from West Africa mostly market themselves as the fastest means of transport in congested cities (see: MAX-"Go", "Go"-kada from Nigeria and "Go"-zem from Togo).

Regardless of their positioning, though, the playbook seems pretty obvious:

- Step 1: Offer transportation as a service and grow as quickly as the market permits — just like Grab and Go-Jek in Southeast Asia

- Step 2: Leverage scale to layer on adjacent services like identity, mobile payments, credit, micro-insurance, etc — just like Grab and Go-Jek in Southeast Asia

- Step 3: Extend services beyond core use case, expand into new verticals, and build ecosystems around your platform — just like Grab and Go-Jek in Southeast Asia

- Step 4: $-$-$-$-$ — just like Grab and Go-Jek in Southeast Asia

To be clear, I've been skeptical about this for some time. Cars are better suited to long trips than motorcycles, and for shorter ones, the question that matters most is liquidity: how quickly will the marginal rider find a driver ready to take them? (You will agree that it makes little sense to wait 7 minutes for a 3-minute trip.) However, just like getting to scale depends on liquidity, liquidity also depends on scale. In other words, these apps must generate enough demand to consume supply as they grow it. Yes, there are use cases for them today (they have users!) but they seem niche, and it's not clear how much larger this will grow over time.

In a society like Nigeria's, for example, a bet on massive motorcycle hailing adoption feels like swimming against the currents of current cultural tropes; cars are social markers, beyond being means of transportation. For those who seek the lowest prices, online hailing might cost too much, and for those willing to pay for the best experience, motorcycles may not be able to deliver it. To be clear, these factors aren't universal: private motorcycles are Southeast Asia's cultural equivalent of the American minivan, but perhaps "Africa" does not look as much like Southeast Asia as we've been led to believe.

This is probably worth a second look — how should we be thinking about it?

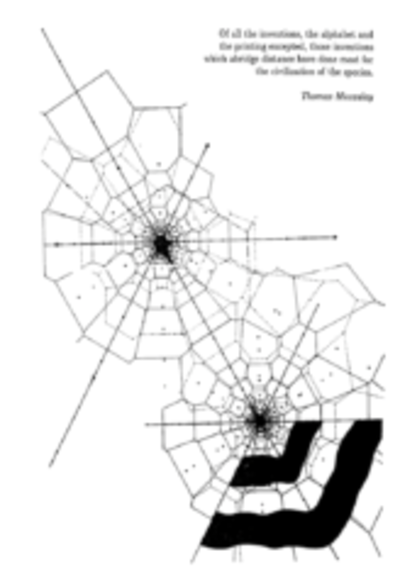

Source: Marchetti, C. (1995). Transport Systems and City Organization: A Critical Review of the Relevant Literature. Report to the Commission of the European Communities Joint Research Center.

Marchetti's Constant, Variable Cities

In a paper published September 1994, Italian physicist Cesare Marchetti posited that 1) all humans have a fixed time 'budget' for daily travel: roughly one hour per day, 2) this budget is innate; it remained fairly constant regardless of era/time period, culture, race, religion, income level, access to technology, settlement pattern, etc., and perhaps most remarkably, 3) it helps determine the size and structure of our territories. Here's an excerpt (emphasis mine):

Now the basic instinct of a territorial animal is to expand its territory [which] means larger resources and opportunities [...] the rationale for accretion is obvious. Exploiting a large territory is also expensive, however, both because [of] the physical exertion of moving over large distances, and [...] the possible threat from enemies and predators.For an animal, and for a pretechnological man, a balance can be struck by adjusting one single parameter: mean traveling time per day. [...] multiplied by the mean speed of movement of a certain animal, it fixes a distance, or a range, that is a territory.

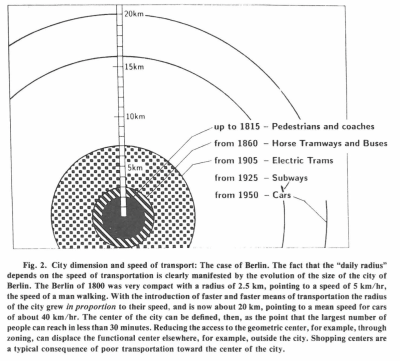

The implication is that each increase in our average travel speed brings with it a proportional increase in the size of our settlements. When we give people faster means to travel, they don't just travel faster — they also travel farther. They cannot 'store' time like they save money, so they reinvest time savings from new advancements into doing more - more valuable - trips until the budget is spent. Take Berlin of 1800, where walking was the dominant mode of transport and the city had a diameter of 5 km; as it turns out, 5 km per hour is exactly the average speed of an adult man walking. As per the diagram below, when faster modes of transport gained adoption, Berlin grew in proportion to their average speed. This goes beyond Berlin, by the way; walking at 5 km per hour implies a territory radius of 2.5 km and an area of about 20 km² — this is exactly the average area we associate with ancient Greek villages today.

Transportation Modes and City Size (Berlin). Source: Marchetti, C. (1994). Anthropological invariants in travel behavior, Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 47 (1) 88. DOI: 10.1016/0040-1625(94)90041-8

Though these ideas are popularly credited to Marchetti, the Italian leaned heavily on the work of another researcher, Yacov Zahavi, about twenty years prior. Zahavi consulted for the US Department of Transportation (DOT) and the World Bank in the 1970s, developing a model he termed the Unified Mechanism of Travel (UMOT). Through the reams of data he collected from cities across the world, the Israeli-born transportation engineer showed that trip makers strive to maximize distance traveled within the constraints of time and money.

For all the obvious reasons, Zahavi could not collect much data about travel budgets in developing countries. Still, there are good reasons to believe trip makers in these nations spend much more of their money and time than their counterparts in the global north:

- Developing countries often have only one or two cities that serve as their administrative, political, or economic backbones, and these cities are far ahead of the others by most indicators of progress (e.g. Lagos, Douala, Nairobi, Kigali, Kampala, Addis-Ababa, etc.)

- This dynamic drives a "pull effect" - massive migration into those city centers relative to their land mass: Nigeria's economic nerve center, Lagos at 1171 km² accommodates 6000! new migrants every day; Nairobi has a population density of 4850 people per square km versus Kenya's 88; Abidjan hosts roughly 21% of Côte d'Ivoire's population despite having 0.65% of its land mass.

- Unsurprisingly, the transport infrastructure buckles under the pressure since these cities i) were not designed to handle such large populations and ii) cannot evolve quickly enough to manage the growth. Case-in-point: the road network in Douala has remained unchanged for the past twenty years despite the population more than doubling in that time. Only 0.5 percent of peripheral settlements have direct access to a paved road.

- As these cities balloon, businesses get situated first, then migrants find whatever housing they can afford — almost certainly in the outskirts. This means that poor newcomers have the farthest to travel every day, despite having the smallest budgets.

The Rise and Rise of Africa's Motorcycle Taxis

This is the backdrop against which the motorcycle taxi industry has seen explosive growth across the continent (2015 market value = $4 billion; 2021 projected = $9 billion). After independence from colonial regimes circa 1960, many African governments took over the provision of public transport from the large bus operators who ran it previously. The consolidation was framed as a show of self-sufficiency, meanwhile transport operations were heavily subsidized and highly regulated. Unsurprisingly:

"[...] subsidies could not be maintained."

The oil shocks of the seventies combined with the creation of increasing numbers of patronage jobs and inefficiency in bus operations increased costs.

Before the turn of the century, many of those state-owned enterprises (e.g., SOTUC in Cameroon, UTC and PTC in Uganda, etc.) had either failed or folded up. And so, paradoxically, the private sector became the dominant supplier of public transport. This collapse of public transit created a demand vacuum that was gradually filled by a mix of individual-owned mini-buses, shared taxis, and - of course - commercial motorcycles. The motorcycles, especially, saw rapid adoption because of their speed, maneuverability, and ability to adapt to shifts in travel demand. And in addition to human transportation, they also helped reduce the cost disadvantage of distance — opening up new avenues for trade and distribution in previously hard-to-reach areas.

This first wave of growth was made possible because soon after World War II, British and American manufacturers lost dominance to their Japanese, Indian, and Chinese counterparts. The latter focused on the vectors Asian and African customers care most about: low purchase price, low cost of ownership, fuel economy, and repairability, while sacrificing engine capacity. Harley-Davidson was the most popular brand in the 1920s, but on the streets of the African cities I've visited lately, the Bajaj Pulsar, Hero Dawn 125, as well as the Suzuki GN125/Hayate GE110 seem to be the most common models. What's interesting, though, is what comes next: the introduction of the [mobile] internet.

African man on a Suzuki. Source: Somewhere on Al Gore's internet

The Networked Okada

Here comes the second wave: what would it mean if you could assume that every motorcycle taxi driver has an internet-enabled smartphone? What could you enable if they were all nodes on a network?

Productivity - It might be strange to think of a motorcycle as a productivity tool, but hear me out: Commuters in developing cities are currently doomed to spend their travel budgets (both time and money) inefficiently. There is value to be unlocked by helping them get more done, and - crucially - they are likely willing to give up some of that value in return. This goes beyond just "beating traffic" or "riding safely" or "going cashless"; it is the *assurance* of all those benefits AND everything else that's enabled once Marchetti's Motorcycles deliver them.

Delivery - A connected network of motorcycle taxis doesn't have to move people alone; it can be leveraged to move things as well. This is important because:

- Transporting things helps increase platform utilization (that is: number of trips per driver per day), which in turn, makes the network that much more valuable for drivers.

- Delivery platforms/marketplaces break the constraint of physical space and help merchants better utilize their fixed assets. Take food delivery as an example: restaurant kitchens can produce much more food than is needed by their walk-in customers. They pay the same amount for the kitchen space no matter how much food they sell, so this creates an opportunity to reduce the unit cost of each serving. This applies beyond food and also allows new kinds of businesses to exist without a physical touch point with their customer.

Agent Networks - In the same vein, we can also think about these motorcycles as a potential agent network or conduit for digital financial services. The platforms would have both a means for distributing their wallets [apps!] and a strong enough use case to cause consumers to fund them [mobility]. The fact that this also helps solve the cash management issue plaguing ride-hailing companies is merely icing on the cake.

- (I haven't looked too closely, but to their credit, SafeBoda seems to be leaning in this direction already.)

- This probably also extends to airtime, content, and who knows what else?

But this analysis is unsatisfying, if compelling. Winning in these markets and doing all the above *depends* on achieving liquidity, and we haven't addressed the question I implied at the beginning of this essay - how do you get to scale in a market where online hailing alone isn't valuable enough to drive adoption?

The answer is irrelevant, and we see why when we examine the two competing market philosophies:

- The demand-centric model says the locus of power is the commuter — just like it is with services like Uber. In other words, the company that aggregates the most users [demand] will incentivize drivers to ride for it and thus, create liquidity for itself through abundance. Here, the business model is obvious: take a cut of the rider fares in exchange for access to the platform. The most obvious risk they contend with is promiscuity: I frequently hail UberBodas in Nairobi, and get picked up by drivers wearing SafeBoda helmets, Taxify reflector vests, and so on. On the other hand...

- The supply-centric model says the driver is the locus of power. Here, companies create their own liquidity through scarcity — recruiting drivers as quickly as they can, locking them into asset financing contracts, and precluding competitors from accessing them. This means that for the duration of the agreements (and likely long afterwards), the drivers wear their branded gear, paint their motorcycles in their colors, use their apps, etc. The most obvious risk is reputational - the platform pays handsomely in brand equity for their drivers' bad behavior, but it's also more difficult to scale: imagine Uber had to help each driver buy a car.

The former philosophy is dominant in East Africa (creating opportunities for third-party financiers), while the latter is more popular westward. As for which of them is more likely to succeed, I leave that as an exercise to the reader. We won't have to wait too long for our first answer because SafeBoda just launched in Nigeria.

Thank you for reading! Please tell someone The Subtext is back.

With love in my heart, and a nervous feeling about this in my belly,

Osarumen.

SELECTED REFERENCES

- Marchetti, C. (1994). Anthropological invariants in travel behavior, Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 47 (1) 88. DOI: 10.1016/0040-1625(94)90041-8

- Zahavi, Yacov. (1976). The Unified Mechanism of Travel (UMOT) Model.

- Marchetti, C. (1995). Transport Systems and City Organization: A Critical Review of the Relevant Literature. Report to the Commission of the European Communities Joint Research Center.

- Osoba, S.B. (2012). A geographical analysis of intra-urban traffic congestion in some selected local Government Areas of Lagos metropolis. Journal of Geography and Regional Planning Vol. 5(14), pp. 362 - 368.

- Olubomehin, O.O. (2012). The Development and Impact of Motorcycles as Means of Commercial Transportation in Nigeria. Research on Humanities and Social Sciences. ISSN 2224-5766 (Paper). Vol. 2, No. 6, 2012.

- Kumar, A. (2011). Understanding the emerging role of motorcycles in African cities: A political economy perspective. SSATP Discussion Paper No. 13. Urban Transport Series.